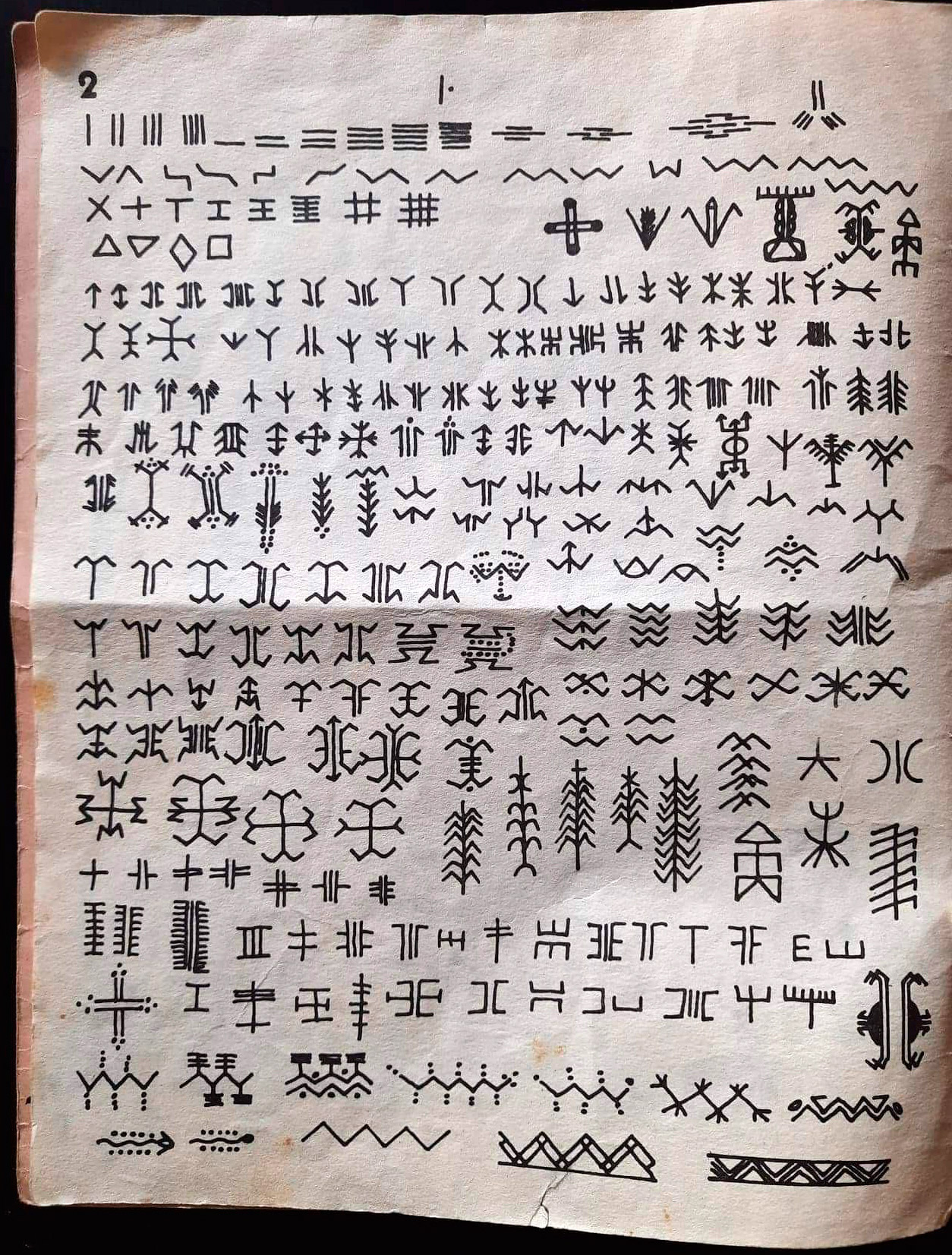

There are more than a hundred thousand Berber motifs. Distributed for millennia throughout North Africa, they are everywhere: on murals, paintings, carpets, pottery, tattoos, carved furniture, brassware, leather goods, jewelry, dresses, architecture, wrought iron...

There are more than a hundred thousand Berber motifs. Distributed for millennia throughout North Africa, they are everywhere: on murals, paintings, carpets, pottery, tattoos, carved furniture, brassware, leather goods, jewelry, dresses, architecture, wrought iron...

Our whole environment is marked by their presence.

It is obvious that all the Berber motifs cannot fit together in such a small work as this one.

Currently the meaning of the symbols has not been our concern. We have, however, noted the very close relation of the basic elements composing the Berber motifs and the Lybic-Tifinagh alphabet. The older the patterns, the more obvious the resemblance.

When a drawing evolves, it becomes a symbol; at the height of its evolution, it becomes part of a writing system.

So far, the research in Berber motifs has been incomplete, but it seems to us as that the peoples of the Mediterranean basin as much as those of the interior of the African continent (N'si bidi of Nigeria and even the Afro-Cuban Anafurauana) could to be, for the most part, the owners of the meanings of the Berber symbols that the major religions are trying to erase from North Africa.

The shapes of the symbols, just like their meaning, have evolved in time and space but remain, once stripped of all sophistication and embellishment, a subject worthy of research. The research to which this collection will make, we hope, its modest contribution.

The lack of fast memory media, like paper, explains why lybic-tifinagh writing could not evolve. The great variety of slow memory media such as pottery and tapestry explains why the Berbers kept the symmetry of their writing, which ended up in the world of decoration. This bilateral or rayed symmetry is copied from nature.

If among the Tuareg the tifinagh writing is still used today, it is because they have a fast medium without memory, which is the desert sand in which they teach their children to write.

The rock paintings and engravings constitute a slow memory medium par excellence.

If the Berbers were perhaps the first to invent writing, on the other hand they did not invent literature, because they had not been able to invent the best of fast memory mediums: paper. But this is another story, because our Atlantis has yet to be built.

When a drawing evolves, it becomes a symbol; at the height of its evolution, it becomes part of a writing system. When the symbol is confined to slow domestic memory media, such as pottery or tapestry, a world ruled by women, it becomes a motif. The beauty of the sign represented by symmetry, repetition and flourishes relegates meaning to the background. The meaning of the sign remains present nevertheless, becoming a code that only women can understand, erasing the border between the real and the imaginary. Magic and superstitions find their outlet there.

The explanation of this essentially feminine symbolism must be taken care of by women researchers in order to obtain the most objective information possible.

For reasons of economy, so that everyone, and especially craftsmen, can acquire this work, we have limited ourselves to black-and-white print. The conventional colors, limited by the palette offered by nature, are of decreasing importance: red ocher, black, kaolin white and yellow ocher. These colors are still used today.

If among the Tuareg the tifinagh writing is still used today, it is because they have a fast medium without memory, which is the desert sand in which they teach their children to write.

—

Adapted from the publication Motifs berbers by Rachid Sadeg, published by Bibliothèque centrale d’Alger, 1991.

Translated from French by The Travel Club.