A travelogue about the infamous mining town of Potosi, in Bolivia, where millions of people have allegedly died extracting silver ore. A once thriving community has been reduced to a dusty, dilapidated town with a lasting hell underneath.

I don't know where I am anymore. I don't know where I'm heading to, either. It seems that the world has seized to be long ago, that the life dried up and left some empty, barren space battered by the wind that blows through window panes and freezes my thoughts. The bus meanders uphill. And all the time I'm followed by the same lifeless emptiness, greyness, dust... As though I feel on my body the pointlessness of moving through nothingness. This is what the world will look like when there's nothing left.

Potosi has filled me with terror from the very beginning. However, it has attracted me at the same time. A meaningless town existing for centuries in the most inaccessible place imaginable, accumulating a history of horror, death and human suffering, but at the same time seducing with its bizarre beauty... We have long ago reached the altitude of 4.000 meters above sea level. I'm thinking that this is the end, that there is nowhere to go from here, that maybe Potosi doesn't exist at all, that it was made up... And as I'm getting more and more convinced that I am really on the road to nowhere, that Potosi is just a horrible legend and a delusion, I start to see the first outlines of the town, as grey and lifeless as everything around it.

In the distance I can make out the reddish hill, Cerro Rico. They say it's a hill that devours people. Cerro Rico is a cradle of this city - it has created it, raised it, only to mercilessly swallow it for centuries, killing it slowly and relishing the endless suffering of those condemned to be its prey. Cerro Rico is not just a hill; Cerro Rico is hell. Cerro Rico is human greed trapped in soil.

Long ago, in 1545, a shepherd named Diego Huallpa grazed his flock of lamas on the slopes of the hill. Diego started a fire to warm himself up; however, the soil around him had a strange glow. Diego inadvertently discovered the biggest silver ore deposit in the history of mankind. The news of the silver quickly reached Madrid. Overnight Potosi sprung up, the highest city in the world, that become one of the largest cities as well, bigger than Madrid itself, with unparallelled wealth. Potosi had pavements made of silver, opulent churches, palaces, theatres, the royal mint, and the constant influx of new settlers looking for riches. Potosi became the symbol of wealth, which is why the Spanish language of the time had a phrase "vale un Potosi" (it is worth a Potosi) for describing immense richness. However, after reaching the summit of its power, Potosi's wealth started plummeting, people started leaving it, and this process of demise has gone on ever since. At one point Potosi was left with only a couple thousand people, and today's Potosi is just a shadow of its former self.

There is a saying that with the silver dug out from Potosi one could build a bridge from Bolivia all the way to Madrid. However, another story says that the bones of those who died in the mine one could build two such bridges. It is believed that eight million people have died in the mines of Potosi, most of them either natives or African slaves. They used to be trapped underground for six months at a time, where they worked 20 hours a day. Some died from exhaustion, some from disease, some were killed in numerous accidents, and a huge number of suicides has been recorded as well. This makes Potosi a site of a forgotten, unknown, hushed up genocide, maybe the largest in the history of mankind.

I don't even know what made me come to Potosi. The notion of this town's history, as well the encounter with its present, fill me with a strange feeling of guilt. Did I come to Potosi only to see something horrible and out of the ordinary, so that I can afterwards tell that I've been in such a place? I know I will leave this town as soon as possible, feeling powerless to do anything, knowing that it was just another place I've seen on my journey... With these thoughts I walked past the city center filled with enormous palaces, churches, monuments. Everything seems monumental, magnificent, but at the same time fills me with loathing. What would somewhere else be just beautiful architecture, in Potosi has a different, sinister dimension.

One of the reasons why many come to Potosi is the possibility to visit the infamous mines. In this world everything eventually ends up as a tourist attraction. I gave up the idea right away. Going to the mine seemed like going to the zoo, with people instead of animals, locked not in cages but in a mine.

I met Helen by accident. It turns out that Helen works as a tour guide, and goes to the mine almost every day. I told her I had been toying with the idea of going to the mine before I came here, but since I've arrived to the city my opinion has changed completely. I am surprised that everyone knows about the inhuman conditions in the mines, yet nothing changes. Here is what Helen told me:

"You know, it is shameful that such a place should exist. I am angry every time I think about it. There are children working there, 15-16 years old. People die at the age of 35... They are simply compelled to work down there. There is nothing else here. The mines are the source of life, but of death as well. At the same time, someone is getting rich from these people's suffering. That is a shame for all of us, for all Bolivia. I would like to write a book about people who live in affluence using these poor souls. I want to write everything I know, and then I will have to leave this country, to leave Bolivia. I already have the title. It will be called "El paraiso del inferno", The Paradise of Hell. Because Potosi brings heavenly life to someone, turning others' lives into hell."

I asked her how she coped with going down into the mine. She told me it was hard, but it was also a chance to convey the truth to others:

"Many people can't even imagine the working conditions there. In a way, apart from what I think about such visits, I also see them as an opportunity to spread the truth about Potosi, to make people aware." She explained to me that the visits mean a lot to the miners; they find them encouraging, and she tries to make them less touristy and as informative as possible. In the end we agreed that I would visit the mine with her the next day, promising that I would write something about it.

July 11 2010. I woke up before seven, tired. I hadn't slept much, the night was cold, so cold that neither my sleeping bag nor the blankets could help me. The altitude also kept breaking my sleep into a series of short half-awake naps. The bed is hard, I have a feeling I'm lying on a wooden plank. The room has no windows. I feel suffocated by the stifling air and I want to leave as soon as possible. At the same time, I don't feel like going out, knowing that the cold wind awaits me. At one point I got out of my cocoon and, as quickly as possible, with my teeth chattering, put on all the clothes I could find near me, and ran out to get some air and see some light again. How is it in the mine?

Documentary "La mina del diablo" (3 parts, 45 min, in Spanish)

I met Helen at eight. We entered a small bus that made its way through narrow, steep streets and stopped in a neighbourhood where poverty was immediately obvious. The miners' market is a place where you can buy all sorts of mining gear, dynamite, pure alcohol, coca leaves, cigarettes - everything a miner needs in his quotidian life. Helen advised me not to buy any of those as gifts for the miners, but to take milk and fruit instead. Milk is the best gift - it is good for the lungs, and almost all the eminers have serious problems with respiratory organs, due to the constant exposure to toxic gases. Most of them die of silicosis, after about 15 years of working in the mine.

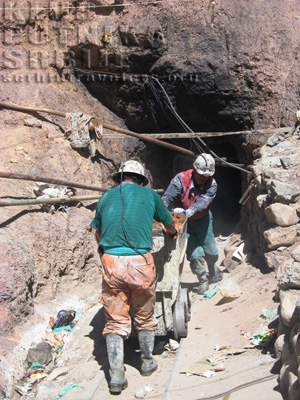

We went over to the shacks, where an Italian guy was waiting for us; Helen will take him to see the mine. We put on uniforms, boots, helmets with flashlights. Then again uphill by bus, to the altitude of about 4.500 meters, past the miners settlement, all the way to the entrance of the mine. Heaps of debris, rusty iron, hills of chat and dilapidated shacks, all that covered in whirls of dust. Some children came to us right away, offering minerals. Sad looks... We walked past women who, their heads completely covered, scoured the debris, looking for the pieces of ore. It was incredibly cold.

In front of a makeshift shop, a group of miners is waiting for their shift. They have torn uniforms, cracked boots and no other equipment. Among them there are kids, boys less than 15 years old. They all know Helen and greet her cheerfully in Ketchua language. They are getting ready to go down in the mine. They will work double shift - 16 hours. I feel bitter. I can't go on.  Still, they are laughing. They are coming to us, telling us their names, shaking hands... Helen gives us a bunch of coca leaves. We have to chew them before entering the mine, to help us cope with the lack of air and the changes in temperature.

Still, they are laughing. They are coming to us, telling us their names, shaking hands... Helen gives us a bunch of coca leaves. We have to chew them before entering the mine, to help us cope with the lack of air and the changes in temperature.

In disbelief I'm looking at the entrance that seems like a little hole in the hill. On the surface there are narrow, rusty rails on which the miners push metal wagons. At first sight, everything seems like in the Middle Ages.

We are entering the mine. There is water under my feet, darkness all around us, and with every step there is less and less air and the shaft narrows down. I can't go any further... I am looking at the people around me, the miners. Some of them are still children. How meaningless this world is... I feel the chill, I loathe myself, every day of my own laments, the lasting injustice upon which, it seems, this world has been built. We are going deeper, and I mechanically follow the steps of those in front of me, in the pitch darkness. From time to time I hit the ceiling with my helmet... We are walking past the shafts that look like mouse holes; it is incredible that, deep inside, there are miners. We stopped for a moment, to listen. The miners from upstairs and those from downstairs communicate by shouting. However, soon we only hear the voices of those closer to us. Helen is upset. She calls the miners, but only those who are upstairs respond. She tells us she is afraid, because there are poisonous gasses downstairs. Once she was there in a similar circumstances and, unfortunately, the worst scenario happened... We will wait.

Long minutes elapse, the time wears on... Now there are no more voices. "Let's hope everything will be fine. They are so young..." Shortly, one of them emerges, telling us with a smile that everything is ok. His colleagues just wandered too far down the underground shaft. We all feel relieved.

When you enter the mine, the familiar world ends. It is the beginning of a world ruled by some other forces, the forces of darkness and El Tio, the Uncle. El Tio is the master of the mine, maybe the devil himself, and entering his kingdom means that one has to please him, to play by his rules and believe in his powers. In the world of the mine, he is the ruler of life and death. Above every shaft there is a figure of his, soaked with the blood of lamas, that are regularly sacrificed to him. There are coca leaves thrown around. The miners deeply believe in his power. They must be in his mercy if they want his protection.

The time wears on. Down the winding corridors, it seems, I arrive to the proper hell. There is little air, the temperature keeps changing, at one moment it is too hot, and a couple of steps later it's cold again... Finally we move towards the exit. I see the Sun again, the light, take in a breath of air. I am happy. I look around myself. I see a barren mountain, tormented people, small shacks. The view is hurting me.

I went back to town. I slipped into my dark, cold room. And I started crying.